This is a post about how things got a little better for me. As some of you know, I contracted Lyme Disease 5 years ago, and since then, things have been quite challenging. I’ve been up and down an enormous number of physical and emotional roller coasters . . . and the roller coaster is by no means through with me yet.

Nevertheless, over the past 6 months my situation has (seemed to) (knock on wood) improve considerably. So I wanted to share my process, in case it can help others.

Over the course of 5 years, I took multiple courses of antibiotics, including 1 month of IV antibiotics. Many of my symptoms improved, but the crushing fatigue, sensitivity to weather changes, and physical limitations continued. I was too woozy to drive safely and too heat-sensitive to travel on foot in Texas, so even on days where I felt a bit better, I couldn’t leave the house under my own power. My quality of life was very poor, and I felt very isolated, lonely, and frustrated.

After 3 years of doctors, tests, and treatments, my point of view changed. Instead of thinking:

“How can I get “cured” so I can feel better, leave the house, be happy and have a life again?”

I thought,

“Given my current situation, how can I feel better, leave the house, be happy and have a life again, even if I’m never ‘cured?’ “

Of course, I still kept up with my appointments, referrals, and so on, but I stopped depending on the idea that they would provide “the answer” that would end my misery. Instead, I started to do two things:

1. Pay Attention

2. Focus on what aspects of my situations I could change to improve my quality of life

Paying Attention: One of the things that was so frustrating for me was that my energy levels were highly variable. I could walk for a mile one day, then nearly pass out the next day after walking only 5 minutes. This made me risk-averse in the extreme, and even less likely to leave the house, because I never knew what could happen. Doctors were no help when I’d say, “Sometimes, I feel woozy and dizzy, but other times I’m fine.”

Now, here we bring in my secret weapon…my super power…the thing about me that strikes fear in my enemies’ hearts:

I’m a really good software tester.

Now, I never thought this particular skill would be something to brag about. In fact, for years it just seemed like I was being paid to have Obsessive Compulsive Disorder — test the same thing over and over, note down every time it’s not perfect, etc.

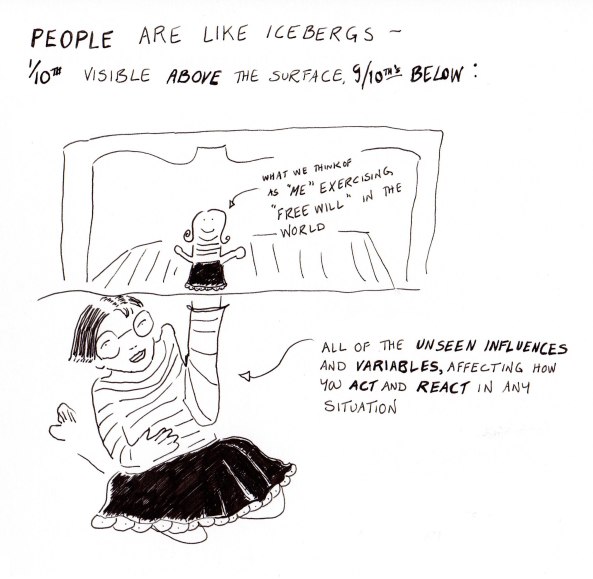

But, it turns out that part of being a good software tester is figuring out how to reproduce a crash that seems to come “at random.” And suddenly, that ‘crash’ wasn’t coming from a computer screen or a mobile device — it was coming from me.

When you’re testing an intermittent crash on a device, what you do is, you broaden your perspective to look at other things that might be influencing the crash. You look at things you normally wouldn’t notice. What other programs do you have open? What angle are you holding the iPad at? What were you doing 10 minutes before the crash happened?

Often when you ask yourself these sorts of questions, you can get to the root of the cause.

So, I started looking at my “crashes” the same way I looked at a software program. I had good days and bad days, and they seemed to be random — but were they?

What was I eating on the day I had a crash? What was I eating for 2 or 3 days before I had a crash?

What was the weather like? What else had I done that day? I looked at any and all variables — anything that could give me a clue.

Slowly and painstakingly, I gathered enough “data points” (ie horrible sucky days) that I got information. I learned, for instance, that eating junk food might affect me one or even 2 days later. My body could absorb the insult of sweets every now and then, but if I ate sugary snacks 2 or 3 days in a row, then I would almost certainly experience a “crash.”

Most importantly, I at last figured out the role temperature was playing in my problems.

For years, I had suffered from extreme heat sensitivity, and that was something I already knew. If the temperature was in the 90’s, I couldn’t go outside.

But, by paying attention to when I felt particularly strong — or particularly weak — I started to gain new information. There was that time I walked for 2 miles without much of a problem. It just so happened that day was in December, overcast with a light sprinkle, and in the 50’s.

There was one day when I walked a half mile outside with no problem, but when I tried to walk on the treadmill in our apartment complex’s exercise room, I grew dizzy and faint after just a few minutes.

I couldn’t understand it, until it finally dawned on me: the days I could exercise tended to be in the fall and winter. And the exercise room, while not broiling by any means, was a little on the warm side.

I wasn’t just sensitive when the outside got hot. I was sensitive to any increase in heat — even the increase caused by my own body when I was exercising. So I needed to be somewhere that, on average, was cool enough to help my body cool down while exercising, because my body had “forgotten” how to cool itself down.

Which meant that I needed to move out of Texas.

This brings us to Step #2:

Focusing on what I could change to improve my quality of life

There’s a story I once heard from a guy I dated. He’d known a woman who was blind for a large part of her life, so she lived in New York City.

“New York City?” I said. “But..the traffic…the people…that would be a terrible place to be blind!”

“On the contrary,” he said. “You can get around by walking, so you don’t have to be able to drive. And, the streets are laid out on a grid…so you can orient yourself by counting the number of blocks. And there are crosswalks at most intersections. New York City is one of the best places a blind person can live, because a blind person can live independently.”

I hadn’t thought about it that way.

So, by moving to New York City, a blind person would…still be blind, of course, but they would gain back the independence that is so often collateral damage to blindness. They could work around their disability, rather than being completely blocked by it.

Maybe there was a way to change my life, so that I could be less limited, too?

I started to think about what I needed, on a very specific level. What triggered my health problems especially? What helped me especially?

I didn’t drive, so my first priority was to live in a place with a walkable neighborhood — where I could afford to live. (Austin has walkable neighborhoods, and affordable neighborhoods, but no walkable, affordable neighborhoods.)

Then I thought about all the other things that would positively impact my health or well-being:

– A place that’s sunny, because grey days make me depressed

– A place less humid than Austin, because humidity exacerbates my joint pain, and I’m allergic to mold

– A place with higher elevation, because I felt very good once when I visited Colorado, and I suspected the mountains had something to do with it

Once I had these criteria, it was like I had a little puzzle, and now I could start on the fun part, which was trying to find cities and towns that fit the puzzle. I started looking at potential candidates:

Santa Fe / Albuquerque — dry, high elevation, but too hot in the summertime.

Colorado — perfect, but too expensive

Los Angeles – cool ocean breezes and temperate days, but too expensive and famously un-walkable

…and so it went. I considered small towns and medium sized cities. When I was curious about housing prices and availability, I would troll through craigslist to get an idea of what was possible.

Eventually, after much trial and error, and a few visits, I settled on Boise, Idaho! Who woulda thunk? Basically, I moved here by spreadsheet, because the city fit all the criteria.

And, so far, it’s been great! Even though it does get hot for 8 weeks in the summer, it still cools down at night, and gives me a few crucial walkable hours even on a hot July day. Here are all sorts of things I’ve been able to do since I moved here:

– Go out and get groceries by myself

– Go to the Post Office by myself

– Take a walk and see something beautiful without asking for a ride

– Get to a doctor appointment by myself

– Live in a gorgeous, well-maintained apartment building near downtown, for less than the cost of a slum in Austin

– Be able to exercise outside and slowly build up my strength, because mornings are dry and cool

– Be restored by clean mountain air

So, even though I’m still ‘sick,’ I’ve changed my situation so that the illness is limiting less of my life. I have more agency, independence, and I’m in an environment that’s helping my body, rather than hindering it.

So far, so good.

So, I hope maybe sharing this process helps somebody else out there…and whatever your struggles…good luck!